These methods will differ among environments so refer to the relevant section:

Water

Pre-Survey Preparations

The methods for the collection of microplastic in marine and coastal waters can have minor variations tailored to specific water compartments i.e., surface, sub-surface and at depth. These methods may also be adapted to collect microplastics within a specific size range.

Sampling design

Before commencing field sampling, it is essential to formulate the research question(s) (see: What are the goals of my research?). Different research questions may require different sampling designs and, likely, different sample collection methods. Furthermore, sampling designs should consider the post-survey requirements, including the time required to accurately process samples, the techniques to be used to analyse them and the units of reporting.

The next step is to define the spatial and temporal extent of the research question. Spatial studies can provide information on the presence of and changes in the distribution of microplastics across sites. Therefore, the sampling design must consider the number and spatial dispersion of the collection sites to answer the research question, site accessibility, and environmental characteristics that may influence results (e.g., the hydrodynamic and depth profile to be surveyed and the expanse of the water body). Temporal studies can provide information on changes in microplastic concentrations at a specific location over time; the sampling design must therefore consider site accessibility across seasons and during/after significant weather events.

Research conducted across spatial and/or temporal scales requires a stratified sampling design that enables an estimate of the true microplastic density (or type, weight, volume) at different scales or “strata” representing clearly defined groups (Quinn and Keough, 2002). Samples should be collected randomly from each group. Stratified sampling should also be used when within-habitat variation is high, and it is not feasible to sample entire sites (CSIRO 2022). Refer to the Survey Design SOP for further details.

Sampling design and approach is dependent on study objectives and will define limitations on the size class of microplastics that can be analysed. For water, sampling can be performed using tow nets, Niskin bottles, submersible pumps, underway vessel pumps or grab samples - see descriptions below. Each mode of water sampling offers a different capability (e.g., in situ filtration of large volumes vs collection of smaller volumes for later processing; the choice being dictated by downstream detection thresholds) and different representativeness (e.g., horizontal vs vertical gradients of the water body, or specific microplastic sizes or types due to density), both of which need to be considered to ensure the research question can be satisfactorily answered (GESAMP, 2019). For example, many tow nets have a 350 µm aperture so smaller microplastics would only be opportunistically sampled, while submersible pumps, Niskin bottles and underway vessel pumps can collect microplastics across the full size range, including smaller microplastics.

The number of samples collected will be determined by the research question as well as the budget, logistics and resources available; with the caveat that a high number of samples allows for greater accuracy (through power and replication) in the estimation of microplastic concentrations in the environment and will ensure greater statistical rigour. It is important to consider what would be an appropriate effect size (i.e. the acceptable difference between the estimate and the true density or volume of microplastics in the water). Before commencing sample collection, a power analysis can be performed to assist in this decision. G*Power (Faul et al, 2007) or pwr package in R (Champley et al., 2020) are suitable for simple sampling designs and can determine the number of samples required to achieve the desired effect size.

Field Procedures

Materials and equipment for collection

The materials and equipment required for collection of water samples varies depending on the type of sampling (Table 1). For volume reduced net tows, submersible pumps and bulk water, the aperture of the filter or net must be recorded. To accurately record the volume of the water sampled a flow meter is required for net and pump devices. GPS values and depth measurements provide additional important contextual information on the site location and details.

Table 1. List of field equipment and materials needed for collection of environmental samples in marine and coastal habitats. Three common methods are considered: volume-reduced net tow filtration, submersible pump filtration and bulk water bottling. Asterisks* indicate essential items.

| Volume reduced net tow filtration | Submersible pump filtration | Bulk water bottling |

|---|---|---|

| Nets (e.g., Manta trawl, Neuston net, AVANI trawl, Bongo net, Hydra-bios nets)*. Net aperture and mesh size must be considered and recorded | Pump device (e.g., built-in underway seawater intake system, portable pump; including pumps deployed in a Rosette device)*. Filter aperture must be considered and recorded. | Sampling bottle of known volume (e.g., glass or plastic bottle of 1 L or more, Niskin and Van-Dorn bottles, including deployed in a Rosette device)*. Volume of sampling bottle must be considered. |

| Flow meter | Flow meter | Volume of water from sampling bottle must be considered and recorded |

| GPS start and end coordinates* | GPS start (and end when applicable) coordinates* | GPS* |

| Depth measurer | Depth measurer | Depth measurer |

| - | Metal sieves (depending on the pump design) | Metal sieves (depending on the sampling bottle) |

| Sampling jar* | Sampling jar* | Sampling jar |

| Labels* | Labels* | Labels* |

| Field observation datasheet* | Field observation datasheet* | Field observation datasheet* |

| Pencils, permanent marker* | Pencils, permanent marker* | Pencils, permanent marker* |

| Metal forceps and/or tweezers | Metal forceps and/or tweezers | Metal forceps and/or tweezers |

| Reagents (ultrapure water, ethanol) | - | - |

General principles

Ocean and coastal environments are dynamic and are inherently highly variable, so it is recommended to sample over time (e.g., seasonally) if feasible, and related to research question (GESAMP, 2019). The rate and extent of seasonal change is a key factor to consider when sampling in the environment. In Australia there are typically four seasons in temperate regions (summer, autumn, winter and spring) or two in tropical regions (wet and dry), but these may be further split based on the local microclimate and different cultural group definitions. When sampling over time is not feasible, recording and reporting information on weather and other environmental conditions at the time of sample collection is crucial for contextual information (see Reporting section).

Airborne and handling contamination is likely to occur during field sampling, so appropriate quality assurance and quality control (QA/QC) procedures must be consistently applied throughout sample collection (see Quality assurance and quality control section). This includes the use of positive controls and blanks during sample collection.

Volume reduced net tows

The survey of water at the surface, sub-surface or at depth, requires the use of compartment-appropriate nets. The methods highlighted below are recommended for surface sampling although can be adapted for mid-column or near ocean floor sampling (Eriksen et al., 2018).

The most commonly used nets to assess surface water are the Manta trawl and the Neuston net, both towed from the side of the vessel, ideally downwind and at a speed of up to 4 knots (Kroon et al., 2018; Viršek et al., 2016). Ideally, sampling should be conducted during calm weather conditions. Manta trawls generally sample the top 15-25 cm while Neuston nets sample the top 50 cm, but both are considered surface tows. Another commonly used net is the AVANI trawl, generally deployed when surveying longer transects as the net can be towed at up to 8 knots. All three net types are relatively inexpensive and simple to operate. Data from all three trawl methods are comparable, as similar types (i.e., positively buoyant) and amounts of microplastic are collected. Whilst reporting information on net configuration is recommended, details on the mesh aperture size are essential and must be recorded against the sample as it defines the lower size category of collected microplastics (e.g., if mesh size is 330 μm, then microplastics greater than 330 μm will predominantly be collected and every item smaller than that should be considered as opportunistically sampled) (Hidalgo-Ruz et al., 2012).

Net deployment procedures need to be tailored to avoid airborne contamination. For example, where possible, the net opening should be protected from air exposure before and post sampling. Along with vessel speed and net opening area, GPS coordinates should be recorded at the beginning and end of each tow to allow calculation of distance travelled, volume sampled, and estimate microplastic concentration (V = Π * r 2 * h) where r = radius of the net and h = distance net towed). To ensure sampling provides an accurate representation of microplastics presence and distribution at the sea surface, at least 1 m3 of water should be sampled – noting this will be dependent on the level of plastic pollution at the sampling site. Note that inferring volume solely based on distance travelled can lead to inaccurate estimations of the volume of water as water current flow is often not measured or accounted for. To achieve greater accuracy in volume estimation a flow meter can be attached to the bottom and/or centre of the net mouth. Replicates at each tow site should be conducted to report data variability. Where collection of replicates is not feasible (i.e., only one tow is conducted before conditions change), this should be clearly indicated, with the knowledge that no standard error or variance can be reported).

Following the sampling event, the entire net must be winched on board and rinsed from the outside using an on-board deck hose (either seawater or freshwater) to transfer trapped contents into the cod-end. Where feasible (e.g., logistically and following QA/QC), any large natural material captured should be removed using metal tweezers and, to dislodge any adhered microplastics, its surface should be rinsed liberally through the net into the cod-end container (the rinsed items can then be disposed of). Physical properties of the rinsed item should be documented. If the sample is dense and rich in organic material, this should be documented to guide the first step in the sample processing protocol, i.e., if chemical digestion is needed to remove smaller organic matter including biofilms (see Processing of microplastics section below). Large plastic debris items captured in the net can also be removed and rinsed through the net into the cod-end container, and stored separately for further analysis. The cod-end contents should then be transferred to a pre-cleaned bottle (e.g., 1-2 L), preserved and stored until analysis (e.g., fridge, 20% ethanol – see storage below). Additionally, the use of positive controls and blanks during sample collection is highly recommended (see Quality assurance and control section).

Before starting the next tow, a clean cod-end, or a used one that has been liberally rinsed with filtered water, should be attached to the net.

Submersible pump sampling

Submersible pumps are another alternative to survey water bodies and are most commonly deployed just below the surface or in deeper water (Rodrigues et al., 2018). Usually, these pumps are systems retrofitted to vessels (e.g., already existing seawater intake systems that are adapted to suit microplastic collection) or portable and able to be deployed via a winch system (Karlsson et al., 2020). While fixed systems have the advantage of minimal handling and can sample along transects (e.g., while in transit or semi-continuously), these can only be used at one depth, and exclude surface microplastics (Schönlau et al., 2020). Portable systems, on the other hand, are suitable for depth profiling and can potentially be deployed from anywhere (i.e., not vessel dependent), but are not well suited to transect sampling. Portable pumps are, however, often expensive and may require skilled personnel to oversee their operation.

The likelihood of airborne contamination occurring while using submersible pumps depends on the pump design, and whether the pumped water is exposed to the air at any stage during collection. To prevent this, many submersible pump systems are designed so that specialised clean filters are only exposed to the air when being removed and replaced. However, some pumps might pump the water over an open sieve, and therefore these samples can be exposed to airborne contamination during collection. When samples are susceptible to airborne contamination during collection, blank controls should be used. These include vials containing ultrapure (e.g., Milli-Q) water that are exposed to air simultaneously with the exposure of samples; these are then passed through every procedural step. Regardless, the use of positive controls and blank controls during sample collection is highly recommended for submersible pump samplings (see Quality assurance and quality control).

The GPS coordinates of the sampling site should be recorded at the beginning of the activity. If a transect is being collected, GPS coordinates should also be recorded at the end of each sampling event to allow for reporting on distance travelled and calculation of the total volume filtered.

The volume of water sampled by submersible pumps is dependent on the system configuration and the depth at which it is deployed. Like for surface water sampling, at least 1 m3 of water is recommended to be collected, allowing first and foremost for further vertical comparison. The use of a flow meter is advised where possible, however, if not available, the volume of water sampled can be calculated using the time the pump is operated (i.e., the sampling period) and the calibrated timeframe in which a given volume of water is pumped. Replicates at each sampling site should be completed to report data variability. Where the collection of replicates is not feasible (e.g., the pump is being used for semi-continuous surveys or technical issues have occurred), this should be recorded, noting that no standard error or variance can be reported.

Samples collected on filters should be immediately removed from the pump and stored in clean containers (e.g., labelled petri dish) to avoid exposure to air. Filters with samples can be stored cold (e.g., -20°C, fridge, on ice – see storage below). When samples are collected over sieves, sampled material must be transferred (i.e., backwashed) into suitable clean containers (e.g., 150 mL vials) using ultrapure water or filtered seawater. These samples can then be preserved cold or in 20% ethanol (i.e., filtered ethanol is added to the sample). If more samples are to be collected via sieving, a new or cleaned sieve should be used.

Fixed submersible pumps are not always able to be thoroughly cleaned (nor visually inspected), especially vessel intake systems. For these pumps, it is important to flush the system well before the start of sampling to ensure any plastics trapped in the system do not cross-contaminate samples.

Bulk water bottling

Water quality sampling is traditionally undertaken with bulk water bottling (e.g., Niskin bottles attached to a Rosette sampler, or bottles directly) deployed in a specific location at a specific defined depth (Nan et al., 2020; Ogunola et al., 2023; Song et al., 2014). This same static sampling method is used to sample microplastics in water and across vertical gradients. When collecting surface water samples, the bottles should be deployed downwind or on the side of the vessel and ideally under calm weather conditions. Collection bottles must be appropriately cleaned before use (e.g., rinsed 3 times with ultrapure or filtered seawater and visually inspected). The configuration of the microplastic sampling system and bottle type can vary, so it is important to record the volume collected and time. The volume required is also dependent on the downstream analysis workflow. For example, if using pyrolysis-GC/MS to detect microplastics, 2 L is appropriate, whereas for other spectroscopy methods 10 L is advised. To limit the risk of airborne contamination, sampling bottles should remain sealed and only be opened and closed when underwater (Samandra et al., 2023). Additionally, the use of positive controls and blank controls during sample collection is highly recommended (see Quality assurance and quality control).

Preliminary processing of these samples is often conducted on the vessel as storage of large volumes is often not possible. The Niskin sample is generally filtered (e.g., over a stainless-steel mesh under vacuum) and the filters are stored in a sealed container (i.e., labelled glass petri-dish) until analysis. When filtering on the vessel is not possible, collected water should be transferred to a pre-cleaned bottle (e.g., 1-2 L), preserved (e.g., fridge, 20% ethanol – see storage below) and stored until analysis.

Storage

Following collection, and regardless of the collection method, all samples should be processed immediately or appropriately preserved until further processing. Although plastic items do not themselves require preservation (i.e., many are expected to persist in the environment for many hundreds of years), organic material is often also part of the collected material. If samples are not preserved this organic matter can degrade and encourage the growth of microbes on the surface of the microplastics, which can impact their retrieval, identification and chemical analysis.

Sample preservation methods include low temperature (e.g., ice, -4°C fridge, -20°C freezers), or chemical treatments (e.g., ethanol, 3% hydrochloric acid), the latter with the caveat that only chemicals that do not impact plastics should be used (Pfeiffer & Fischer, 2020). Where possible, preliminary processing to clarify samples and enhance their long-term storage should be applied. For example, filtration can reduce volume, washing with ultrapure water (e.g., Milli-Q), <20% ethanol, or sonication (three cycles for five minutes each based on Kaiser et al., (2017)), can dislodge any biofilms attached to the microplastic surface, thereby enhancing buoyancy and contributing to more accurate and effective separation, identification and subsequent analyses.

In instances where immediate sample preservation or processing is not feasible, considerations need to be made for the influences that biological material can have on the retrieval and identification of microplastic particles.

Sample processing and analyses

After collection of the water samples, the microplastics need to be isolated for quantification and identification. Following good laboratory practice, a sample audit should be conducted, and all relevant environmental parameters and sample information entered into a project database or spreadsheet.

In this section, we briefly summarise the equipment and materials needed to process water samples. As well as briefly describe the steps to separate and quantify microplastics, physical and chemical characterisation and QA/QC.

Processing of microplastics (1 μm - 5 mm)

Equipment

Material

- Glass Petri dishes and beakers

- Metal forceps/tweezers

- Stainless steel filters

- Millipore gridded membrane (nitrocellulose filters)

- Metal sieve (sieve diameter and mesh aperture size need to be reported; the latter to understand the lower size limit)

- Density meter (for testing the density of the separation reagent)

Reagents

- Ultrapure water (e.g., Milli-Q)

- Preservation reagent (e.g., 10-20% ethanol, 70% ethanol)

- Density separation reagent (e.g., sodium chloride, sodium iodide or other outlined below)

- Chemical digestion reagents (e.g., 30% hydrogen peroxide, 10% potassium hydroxide or other outlined below)

All reagents and solutions should be filtered (<20 μm) before use, excluding the ultrapure water, which is already filtered.

Instruments

- Temperature controlled oven (optional)

- Orbital shaker (optional)

- Heated stirring plate (optional)

- Glass magnetic stirring rod (optional)

- Laminar flow (recommended)

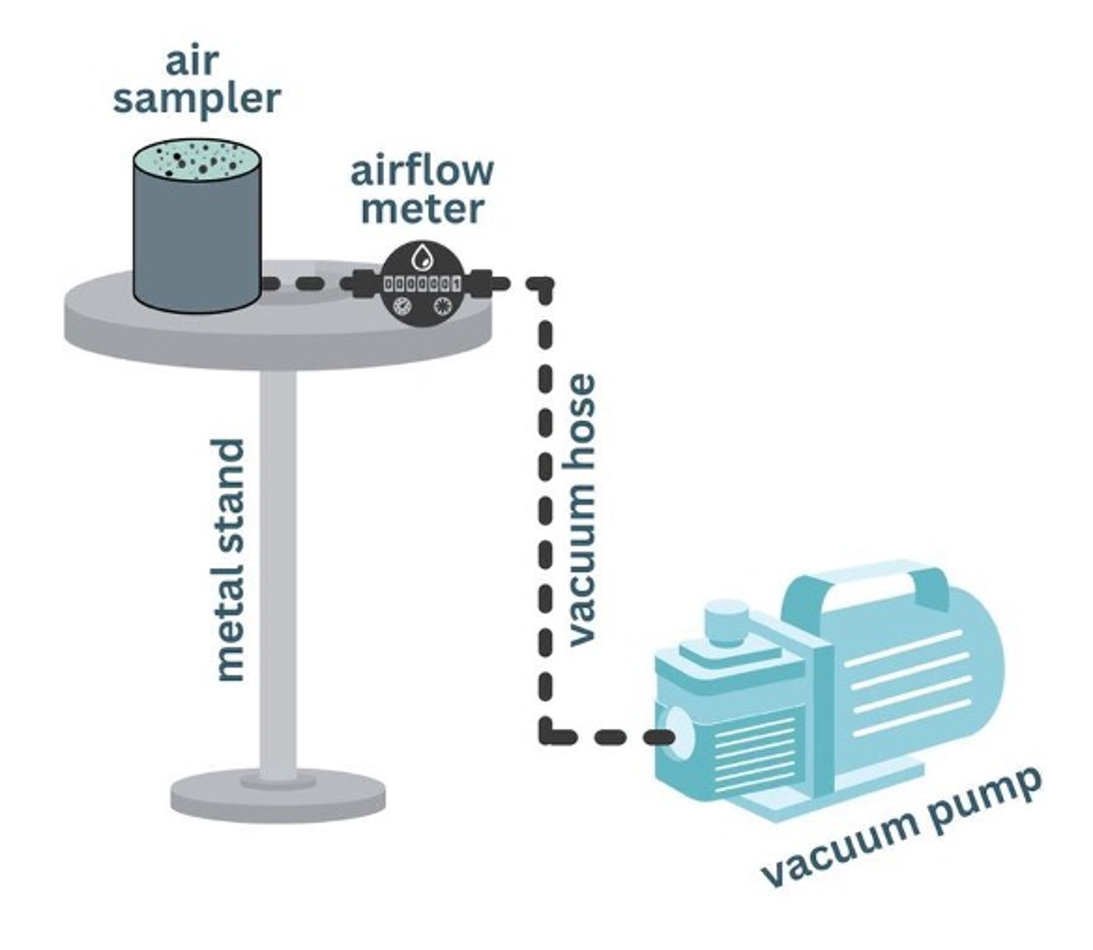

- Filtration equipment (glass or stainless steel), including vacuum pump

- Stereomicroscope

- Polymer identification instrument (e.g., FTIR, μ-FTIR, ATR-FTIR, RAMAN, py-GC/MS)

Pre-treatment and procedures for microplastic separation

Water samples with low organic content

Water samples that visually appear clear can be fast-tracked through the isolation process to either density separation or filtration, with no chemical digestion needed. If preserved frozen, samples (still covered) should first be defrosted at room temperature. If preserved in a chemical solvent (i.e., 20% ethanol), care should be taken following the chemical solvent’s Safety Data Sheet (e.g., regarding PPE and others).

Water samples with medium/high organic content

If the water sample contains phytoplankton, zooplankton or other organic matter that hinders the retrieval of microplastics, a clarification step is required prior to filtering. This clarification can be achieved using density separation (see below), but for samples with higher organic content, preliminary chemical digestion may be required (see below).

Chemical digestion

Chemical digestion can be applied as a first step to separate microplastics from seawater. There are a range of different chemicals that are appropriate, depending on research question, laboratory facilities and reagent availability (Table 2). The type of chemical digestion chosen is a compromise between efficiency, cost, and the known health and safety risks and potential for polymer degradation (Di Fiore et al., 2024; Miller et al., 2017; Pfeiffer and Fischer, 2020)(Table 2).

As an example, described below is a procedure that has been applied to facilitate the chemical digestion of a surface water samples with a high algae content. Potassium hydroxide (10% KOH) was added directly into the filtered seawater samples and then heated to a maximum of 40°C in a controlled oven for up to 72 hours. Where the digestion rate of the organic matter was slow, i.e., there was still organic material present after 72 hours, a second digestion method using hydrogen peroxide (H2O2 30% w/v) was applied. The sample was again agitated at 40°C on a temperature-controlled magnetic stirrer in a fume hood and the reaction was allowed to go to completion (follow Safety Data Sheet for all chemicals). Thereafter, samples went through density separation.

Table 2. Summary table of digestion reagents, their concentrations, advantages and limitations. Based on: Di Fiore et al. (2024) and Pfeiffer and Fischer (2020).

| Digestion | Recommended concentration | Advantages | Limitations | Degradation of polymers? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) | 15-30% | Efficient, cheap | Corrosive, hazardous | Yes, at high concentrations |

| Hydrochloric acid (HCl) | 20% | Efficient, cheap | Corrosive, hazardous, toxic, can degrade polymers | Yes |

| Nitric acid (HNO3) |

Weak | Efficient, cheap | Corrosive, hazardous, causes discolouration of plastics, can degrade some polymers | Yes |

| Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) | 1 M | Efficient | Corrosive, hazardous, can degrade some polymers | Yes |

| Potassium hydroxide (KOH) | 10% | Efficient | Corrosive, hazardous | Yes, at high concentrations |

| Enzymatic digestion | Safe, efficient | Expensive, time intense | Yes |

Density separation

For large water samples density separation can be applied as a first step to separate microplastics from seawater or following chemical digestion. Concentrated water samples are resuspended in the brine solution of choice with less dense materials (e.g., microplastics) floating and becoming separated from denser materials (sediment, debris, others) present in the matrix. There are a range of different reagents that can be used for density separation. These differ in their density, and each has advantages or limitations associated with efficiency for microplastic recovery, varying levels of toxicity, and price range (Rani et al., 2023) (Table 3). Commonly used reagents include sodium chloride, sodium tungstate dihydrate, sodium bromide, sodium polytungstate, lithium metatungstate, zinc chloride, zinc bromide and sodium iodide. The effectiveness of reagents is polymer dependent, e.g., higher density reagents are more effective at removing more dense polymers. The density of the final solution used must be reported, as it will dictate which plastic polymers can or cannot be retrieved with this methodology.

Note, samples that have been preserved (e.g., 20% ethanol) or chemically digested, may still contain some of the reagents and there is a risk that these will react with the density separation reagents, therefore, it is important to first neutralise the sample. The preserved or digested sample must be rinsed liberally with ultrapure water onto a filter or sieve before the density separation step. Always refer to the Safety Disposal Sheet of the chemical reagents for appropriate use and disposal.

To achieve density separation, the reagent should be added to the sample first, and then stirred (e.g., with a metal spoon or glass rod) and the solution allowed to settle. Stirring and settlement periods can vary based on sample complexity, and should be tailored with preliminary and spike recovery tests. Once a sample is completely stratified, the established supernatant should be poured over an appropriate filter (i.e., metal mesh, glass microfiber, silicon coated filter) using a filtration device (preferably metal or glass). The walls of the sample container should be rinsed liberally with ultrapure (e.g., Milli-Q) or filtered water to ensure all microplastic items are transferred. The filter should be stored in a labelled petri dish and covered with a glass lid. To identify microplastics, captured items should be observed under a microscope using any one of the microplastic quantification steps outlined below.

Table 3. Commonly used density separation reagents, highlighting their advantages and limitations.

| Density separation reagent | Density of solution | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium chloride (NaCl) | 1.2 g cm-3 | - Recovers low density polymers (e.g., PE, PS, PP, PMMA, PC) - Cost effective - Non-toxic - Readily available |

- Less efficient at recovering high density polymers (e.g., PC, PU, PET, PVC, PTFE) |

| Sodium tungstate dihydrate (H4Na2O6W) | 1.4 g cm-3 | - Recovers low density polymers (e.g., PE, PS, PP, PMMA, PC) - Cost-effective - Non-toxic |

- Less efficient at recovering high density polymers (e.g., PC, PU, PET, PVC, PTFE) |

| Sodium bromide (NaBr) | 1.37 g cm-3 | - Recovers a wide range of polymers - Non-toxic |

- Expensive |

| Lithium metatungstate (Li2O13W4-24) |

1.62 g cm-3 | - Recovers a wide range of polymers | - Expensive - Unknown effect on polymers |

| Zinc chloride (ZnCl2) | 1.5 - 1.7 g cm-3 | - Recovers a wide range of polymers | - Expensive - Toxic to the environment |

| Zinc bromide (ZnBr2) | 1.71 g cm-3 | - Recovers a wide range of polymers | - Expensive - Toxic to the environment |

| Sodium iodide (NaI) | 1.6 - 1.8 g cm-3 | - Recovers a wide range of polymers | - Expensive - Toxic to the environment |

| Calcium chloride (CaCl2) | 1.5 - 3 g cm-3 | - Recovers a wide range of polymers | - Expensive - Toxic to the environment |

| Potassium Iodide (KI) | 1.7 g cm-3 | - Recovers a wide range of polymers - Non-toxic |

- Expensive |

Filtration

Water can be poured through the filter or sieve and gravity will drain the sample, or a vacuum pump can be used to accelerate the filtration and if there is a high particulate content. The configuration of the filter or sieve can vary, i.e., an individual filter or sieve can be used, or a tiered filtration unit (Schlawinsky et al., 2022). Either way, the smallest filter size must be recorded, as this will define the smallest microplastic sample that can be collected (e.g., if the sieve is 100 μm, microplastics smaller than 100 μm will not be accurately or consistently captured).

For samples preserved in a chemical solvent, the dilution of the preservation chemical should be such that there is <1% in the final washings. Crystallization and retention of inorganic salts in the sample solids can occur after filtering and may hinder both the physical and chemical analysis of microplastics. To prevent this, it is crucial to thoroughly and liberally rinse the filtrate with ultrapure water (e.g., Milli-Q).

Following filtering, filters with solids can be stored in labelled glass jars or covered petri dishes until microscope examination. The filtration unit should then be thoroughly rinsed with ultrapure water (e.g., Milli Q) and carefully inspected to ensure no residual solids remain and to prevent cross-contamination of the next sample.

Sediment

Pre-Survey Preparations

The methods for the collection of microplastics in marine, coastal, and riverine sediment can vary depending on the sediment composition (i.e., grain size, organic content) and environment (i.e., subtidal - always submerged; intertidal - the area between high and low tide; and supratidal - the area above the high tide line and only flooded occasionally during storms).

Sampling design

Before commencing field sediment sampling, it is necessary to formulate the research question(s) (see What are the goals of my research?). Different research questions may require different sampling designs and, likely, different sample collection methods. Furthermore, sampling designs should consider the post-survey requirements, including the time required to accurately process samples, the techniques to be used to analyse them and the units of reporting.

The next step is to define the spatial and temporal extent of the research question. Spatial studies can provide information on the presence of and changes in the distribution of microplastics across sites. Therefore, the sampling design must consider the number and spatial dispersion of the collection sites to answer the research question, site accessibility, the zone to be surveyed (i.e., intertidal vs supratidal), the site profile, geographical and oceanographic features, accumulation dynamics, the expanse of the area, and other environmental characteristics that may influence results. Temporal studies can provide information on changes in microplastic concentrations at a specific location over time, therefore the sampling design must also consider site accessibility across seasons and during/after significant weather events. For example, coastal environments are prone to significant shifts and fluxes in features (i.e., coastal erosion or submergence) due to rises in sea levels (i.e., king tides) and changes in wave action and currents from events such as flooding and cyclones.

Research conducted across spatial and/or temporal scales requires a stratified sampling design that enables an estimate of the true microplastic density (or type, weight, volume) at different scales or “strata” that represent clearly defined groups (Quinn and Keough, 2002). Samples should be collected randomly from each group. Stratified sampling should also be used when within-habitat variation is high, and it is not feasible to sample entire sites (CSIRO 2022). Refer to the Survey Design SOP for further details.

Sampling design and approach is dependent on study objective and the environment being sampled, e.g. quadrats or transects for intertidal habitats, grabs, quadrats, or cores for subtidal habitats (see descriptions below). Budget and logistical constraints also need to be considered as does the translation of methods for uptake by citizen science monitoring programs (which are now a key vehicle for conducting global surveys). Sampling approach can also define limitations on the size class of microplastics that can be analysed.

The number of samples collected will be determined by the research question as well as the budget, logistics and resources available; with the caveat that a high number of samples allows for greater accuracy (through power and replication) in the estimation of microplastic concentrations in the environment and will ensure greater statistical rigour. It is important to consider what would be an acceptable difference between the estimate and the true density or volume of microplastics (i.e., the effect size). Before commencing sample collection, a power analysis can be performed to assist in this decision. G*Power (Faul et al., 2007) or pwr package in R (Champley et al., 2020) are suitable for simple sampling designs and can determine the number of samples required to achieve the desired effect size.

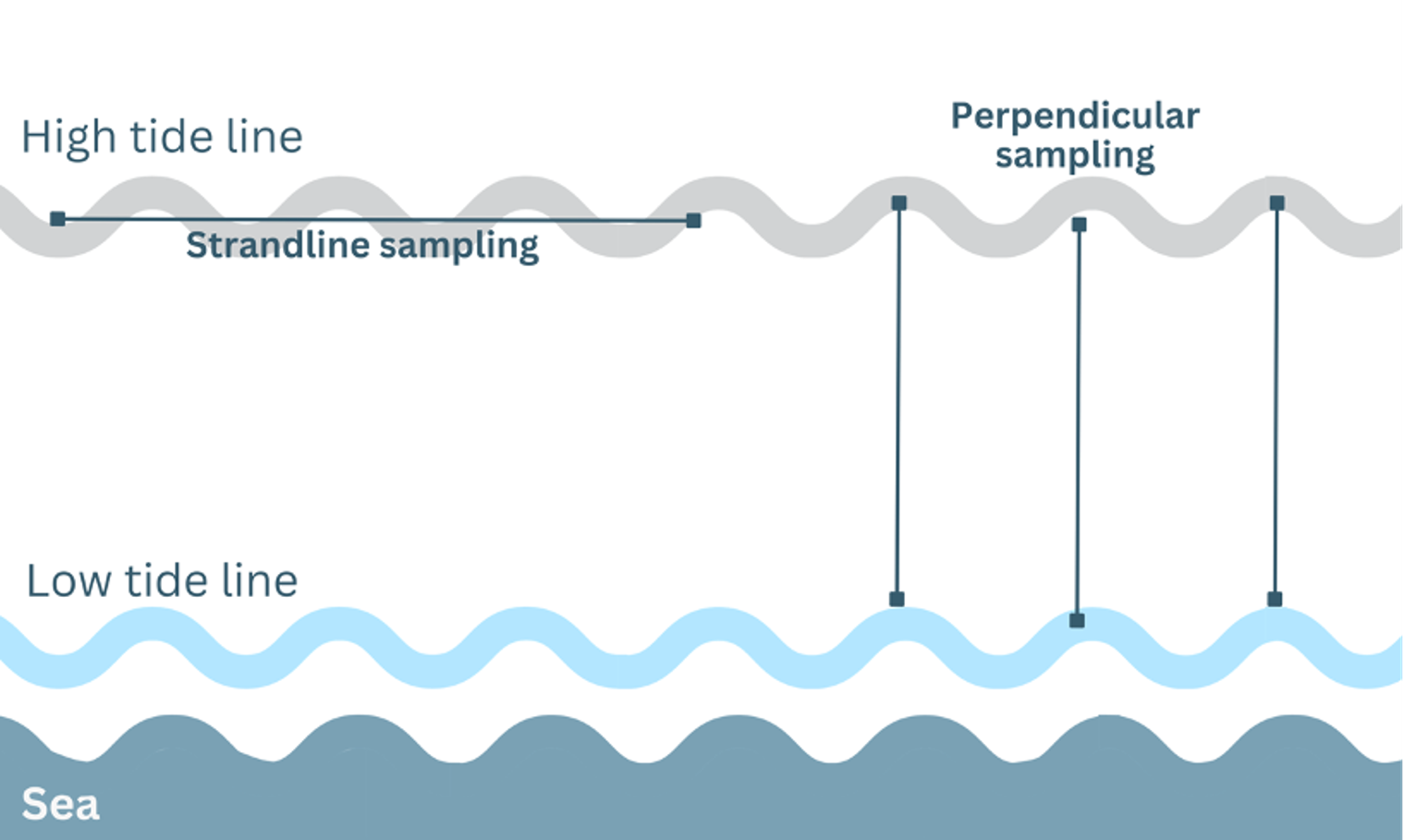

There are two main approaches when examining transects for microplastic presence in subtidal, intertidal or beach environments (note this can include monitoring the entire transect, or quadrats along the transect, depending on the research question). The first is the parallel to shoreline, including the ‘strandline’ approach (which will record debris from the last high tide), where a set length of the beach is measured, and microplastic quantified (example in Figure 2, shows collection along the high tide line). The second is the perpendicular to shoreline approach, which records changes in microplastic density towards the tideline if/when the transect is surveyed in discrete sections. Both strandline and perpendicular methods are appropriate, and their use will depend on the research question. It is important to record details of environmental conditions, physical features at the site (e.g. sandy vs rocky beach, long beach vs small cove), and weather conditions (e.g., tides, storm surge, wind, wave action) (see environmental variables and the Reporting information section).

It is essential to record information on sampling effort as this can create variability in the results. This is particularly important with community-led beach surveys (e.g., citizen science monitoring programs), where there is variation in the number of people participating across time, how many hours are spent searching, level of competency, and area searched. These are important aspects that should be considered during sampling design and prior to commencing collection. Whilst other methods (e.g., grabs) are not impacted by the number of surveyors, it is essential that the number of samples and replicates are clearly identified.

Figure 2. Sampling approaches for microplastic monitoring in intertidal environments.

Field Procedures

Materials and equipment for collection

Table 4. List of equipment and materials required for field sample collection in intertidal/supratidal and subtidal habitats. Asterisks* indicate items that are essential for microplastic sampling.

| Intertidal and supratidal | Subtidal |

|---|---|

| Measuring tape* | Grab or coring device (e.g., box corer, van Veen grab, sediment corer) * |

| GPS start and end coordinates* | GPS start and end coordinates* |

| Quadrat* | Quadrat (for scuba diving survey) |

| Metal shovel or spoon* | Metal shovel or spoon |

| Depth gauge | Metal ruler |

| Stainless steel sieves or filters | Stainless steel sieves or filters |

| Glass petri dishes | Glass petri dishes |

| - | Syringe and suction tube* |

| Glass jars, aluminium tray or sterile press-and-seal plastic bags or paper envelopes (for dry sediment samples) * | Glass jars or zip lock plastic bags* |

| Labels* | Labels* |

| Field observation datasheet* | Field observation datasheet* |

| Pencils, permanent marker* | Pencils, permanent marker* |

| Camera | Camera |

| Glass filtering flask | Glass filtering flask |

General principles

Ocean and coastal environments are dynamic and can be highly variable, so it is recommended to sample over time (e.g., seasonally) if feasible. Seasons may vary depending on the region being sampled, in some areas of Australia there will typically be four seasons (summer, autumn, winter and spring) or two (wet and dry), but these may be further split based on local microclimates and different cultural group definitions. When sampling over time is not feasible, recording and reporting information on weather and other environmental conditions at the time of sample collection is important for contextual information (see Reporting section).

In the field during intertidal/supratidal, subtidal, and other environments, transects for perpendicular or strandline sampling (depending on the research question) should be measured for length. Additionally, GPS coordinates at both the beginning and end of the transect recorded. Photographs of the sampling transect should be taken. A randomised and stratified sampling design should be implemented, with a minimum of three replicate samples taken randomly along the transect. It is important to note, however, that the number of replications needed along the transect will depend on the microplastic load and the accumulation dynamics of the site. If there are large abundances of microplastic counted, three replications are needed, however, if there are low counts of microplastics, variations in the environmental conditions (e.g., variations in sediment type or grain size across transects), or other confounding factors, more replications are required. Likewise, sampling locations can be randomised (i.e., using a random number generator) along the transect. The GPS coordinates for each sampling location must be recorded.

Airborne and handling contamination can occur during field sampling, so appropriate quality assurance and quality control (QA/QC) procedures must be consistently applied throughout sample collection (see Quality assurance and control section). This includes the use of positive controls and blanks during sample collection.

Intertidal/supratidal

The collection methods employed in the intertidal and supratidal zones are similar. There are two main approaches for investigating microplastics in these two zones - standing stock assessments, and accumulation assessments. The first (standing stock assessment) involves collecting or counting the microplastic pieces which are already present on the beach (Fisner et al., 2017). This type of survey method gives a value about the microplastics at a given time in a given area. The latter approach (accumulation assessment) involves clearing the plastic away from the tideline initially, and then counting and/or collecting the microplastics that are carried by the waves (Galgani et al., 2013; GESAMP, 2019). This allows for information on the microplastic accumulation from the water.

There are a number of ways to count and/or collect microplastics, depending on the research objectives in intertidal and supratidal zones. Investigation of visible microplastics (1 mm - 5 mm) is usually done by counting the number of microplastics within a defined quadrat (e.g., 25 cm x 25 cm, 50 cm x 50 cm or other) often along a transect, with microplastics counted visually from standing height (estimated to be one metre directly above). This method does not require handling of the sediment, however, if desired, the top layer (1-5 cm) of sediment from the quadrat can be collected and sieved (i.e., using a 1 mm aperture metal sieve) to capture microplastics for subsequent chemical analysis.

If microscopic microplastics (1 μm - 1 mm) are to be counted the sediment will need to be collected and transported for further processing. The sediment can be collected in a number of ways and is dependent on the site accessibility and storage and transport capacity. Recommended approaches include, collecting the top layer of sediment (between 1 - 5 cm) within the entire quadrat using a metal shovel and depth gauge (Piperagkas et al., 2019; Wessel et al., 2016). The size and depth of the sample collected should be recorded, along with sample mass (can be measured retrospectively). Alternatively, a quadrat can be placed and randomised replicate samples within the quadrat collected (e.g., using a small corer, vial, or shovel). A minimum of three replicates are recommended to allow for variance to be calculated within each quadrat.

Subtidal

There are generally five approaches used to collect subtidal sediment – grab samplers, core samplers, dredge samplers, or quadrats via SCUBA and Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs).

The depth and sediment type to be collected, and the mode of collection, will depend on the research question. Where possible, retrospective sampling design needs to be optimised to collection mode, i.e., whether the mode of collection is manual or automated, and to the site.

If using grab, core, dredge or ROV samplers, consideration must be given to the grain size, the sampling regime (i.e., top 5 cm of sediment surface vs subsurface cores), the effort required to sample, and the potential for incidental resuspension of microplastics, which can result in an underestimation of microplastic concentrations. In some cases, collections by grab can be further subsampled using a corer.

Other environments

The methods outlined above can be tailored and transferred to additional land and aquatic habitats, both freshwater, estuarine, and marine. For land habitats, (e.g., sand dunes beyond the supratidal zone, mudflats, riverbanks, mangroves) the intertidal/supratidal methods should be followed. While for aquatic habitats (e.g., river sediment, estuaries, coral reefs) the subtidal methods are likely more appropriate (Skalska et al., 2020). When tailoring these sample collection methods, the sampling design should always be considered, and the modified method validated. Likewise, the accessibility and features of the site may dictate the ability to perform transects, so changes may be required. Overall, providing detailed information on sample collection is an essential step to ensuring broad study comparisons (see Reporting information).

Storage

Following collection, and regardless of the collection method, all samples should be processed immediately or preserved until post-survey processing procedures can be completed (see Quality assurance and quality control section). In specific circumstances samples may need to be frozen (e.g., for cores, and to minimise disturbance of layers) or dried to reduce the likelihood of microbial and algal growth (Adomat et al., 2022). Storage containers and vials should only be opened whilst transferring the sample to minimise any extraneous airborne contamination.

Where possible, preliminary processing either in the field or as soon as possible after collection should be applied to enhance their long-term storage. For example, elutriation and/or density separation methods can quickly reduce sediment mass, but note both require optimising to the sediment type.

Although plastic items do not themselves require preservation (i.e., many are expected to persist in the sediment for many hundreds of years) organic matter is often also part of the collected material. If samples are not preserved, this organic matter can impact the processing, retrieval, identification and chemical analysis of microplastics. Where needed, samples should be stored cool at -4°C (limited time) or frozen at -20°C or -70°C (for cores). In instances where immediate sample preservation or processing is not feasible, considerations need to be made for the influences that biological organisms can have on the retrieval and identification of microplastic particles.

Sample processing and analyses

After the collection of sediment samples, the microplastics need to be isolated for quantification and identification. Following good laboratory practice, a sample audit should be conducted, and all relevant environmental parameters and sample information entered into a project database or spreadsheet.

This section briefly summarises the equipment and materials needed to process sediment samples and describes the steps to separate and quantify microplastics, including their physical and chemical characterisation and QA/AC considerations. These procedures can be undertaken either in the field or laboratory, depending on environment, safety considerations, and available facilities in the field.

Processing of visible microplastics (1 mm - 5 mm)

Equipment

Material

- Glass Petri dishes and beakers

- Metal forceps/tweezers

- Metal sieves [sieve diameter and mesh aperture sizes need to be reported; the latter to understand lower size limit (e.g., 1 mm)]

Reagents

- Density separation solutions (e.g., Sodium chloride, Potassium iodide, Zinc chloride). See Table 5 below for details

- Chemical digestion reagents (e.g., 30% hydrogen peroxide, 10% potassium hydroxide)

- Ultrapure water (e.g., Milli-Q) or filtered water

Instruments

- Stereomicroscope (recommended, but will be essential for microplastics <1 mm)

- Polymer identification instruments (e.g., FTIR, u-FTIR, ATR-FTIR, RAMAN, py-GC/MS, LDIR) (desirable for polymer type)

Procedure

Sediment should be sieved through an appropriately sized metal sieve (e.g., 1 mm) and retained microplastics sorted, counted, and identified (see Microplastic characterisation and quantification). Larger natural debris (i.e., algae, shell, sticks, biota) should be removed with forceps or tweezers and liberally rinsed with ultrapure water (e.g., Milli-Q) or filtered water over the sieve to remove any microplastics adhering to their surface. It is recommended a microscope be used where feasible.

Sediment type, range in grain size, and levels of organic matter can influence the ease of sieving and the downstream separation and identification of microplastic. In the case of finer sediments (i.e., silt, mud, clay), density separation or pre-treatments (i.e., chemical digestion) may assist in separating the microplastics from the sediment and/or organic matter. See below for more details on density separation and chemical digestion. While recommended, it may not always be feasible to include these steps, e.g., in field surveys associated with citizen science monitoring programs. In these and other circumstances, it is critical to accurately report collection information and the minimum size range of plastics that can be captured and visually detected (see Reporting section).

Processing of microscopic microplastics (1 μm - 5 mm)

Equipment

Materials

- Glass Petri dishes and beakers

- Metal forceps/tweezers

- Stainless steel filters

- Metal sieves (varied sized, sieve diameter and mesh aperture size need to be reported; the latter to understand lower size limit (e.g., 1 µm))

- Acid-resistant plastic box with lid

Reagents

- 30% w/v hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) - for organic matter removal

- Fenton’s reagent (H2O2 and FeSO4)

- Density separation solutions (e.g., Sodium chloride, Potassium iodide, Zinc chloride. See Table 2 below for details on appropriateness of different reagents).

- Ultrapure water (e.g., Milli-Q) or filtered water

All reagents and solutions should be filtered (<20 μm) prior to use, excluding the ultrapure water, which is already filtered.

Instruments

- Laminar flow cabinet (optional)

- Filtration equipment, including vacuum pump

- Stereomicroscope (essential for microplastics <1 μm)

- Oven or freeze drier

- Polymer identification instruments (e.g., FTIR, μ-FTIR, ATR-FTIR, RAMAN, py-GC/MS, LDIR)

Procedures

Sediment drying

Depending on the processing method and units of reporting, sediment samples may need to be dried, either in a freeze drier (loosely covered), or in a low heat oven (covered). The time and temperature required to dry the sample will vary depending on the sediment type, grain size, organic load, sample mass, and mode of drying. Caution should be taken when heating sediment samples as plastics may be impacted at temperatures above 40°C. Following drying and depending on the research question, the sample can be homogenised by sieving with a mechanical mixer or hand mixing (with care to ensure no fragmentation of plastic occurs). For larger samples, a subsample of a specific weight (e.g., 100 grams) can be collected (i.e., using a metal corer), ideally this should be done in triplicate to ensure sample representativeness.

Chemical digestion

A pre-treatment to remove organic matter from organic-rich sediments is recommended. This aids in the clarification of the sample and means that the subsequent application of density separation solutions is likely to be more effective, it also allows for the use and re-use of more expensive density separation solutions which are often needed to isolate higher density microplastics.

There are a number of methods that can be used to digest sediment bound organic matter including 30% w/v H2O2 solution or Fenton’s reagent (H2O2 and FeSO4; the ferric ions act as a catalyst). However, care should be taken when considering degradation of polymers when certain reagents are left for periods of time or temperatures (Di Fiore et al., 2024; Miller et al., 2017; Pfeiffer and Fischer, 2020). When using H2O2 and Fenton’s reagent, the solution should be added to the sediment, mixed with a metal spoon or glass rod for one minute and left covered (e.g., watch glass) for up to 18 hours (depending on the amount of organic matter). To increase the efficiency of this reaction, the solution can be heated to 40 - 50°C to enhance the digestion process (note that temperatures above 40°C may impact and degrade particular polymers more than others). Based on time (i.e., 18 hours) or clarity (i.e., no visible organic matter remaining) or temperature (the reaction is exothermic and will cool once digestion is complete), the reaction should be quenched by washing thoroughly with ultrapure (e.g., Milli-Q) or filtered water (i.e., formation of carbon dioxide bubbles stops). Fenton’s reagent can be challenging with the efficiency of the digestion dependent on the pH of the sample, therefore prior to use further reading on the use of Fenton’s reagent is recommended (e.g., Tagg et al., 2017).

Elutriation

Where organic content is not high, an elutriation pre-treatment to process larger masses of marine and coastal sediments is recommended. Elutriation is a process designed to separate lighter particles from heavier ones, using an upward stream of gas or liquid (Claessens et al., 2013; Hengstmann et al., 2018; Kedzierski et al., 2016; Zhu, 2015), thereby rapidly reducing the initial volume of the sediment sample and concentrating finer solids and debris for subsequent density separation. To separate microplastics from larger sediment samples (i.e., >500 g), samples can be transferred into a tall column (e.g., ~1 m, and preferably of glass or stainless steel) connected to a freshwater source (via a tap at the base of the column). The water flow is controlled through a valve handle and should be monitored by a flowmeter. To avoid the introduction of potential contaminants from the plumbing, the water must first pass through a filtering system (e.g., 1 µm cartridge filter)before entering the base of the column. The water then passes through a 26-µm mesh that ensures a homogeneous distribution of water flow inside the column. When the tap is open, the sand becomes fluidised and the lighter particles are carried to the top of the column. As the water flows over the outlet any floating solid material is collected on a metal sieve with the desired µm aperture (e.g., 10 µm). The optimal flowthrough is dependent on the sediment granulometry and should be determined by spiking experiments (e.g., for a 1 m column, a 1400 L per hour water flow for 3 minutes is optimal for beach sand). The loaded sieves should be covered (e.g., with aluminium foil) and transferred to the laboratory for further processing via density separation.

Density separation

To separate microplastics from sediments, samples are resuspended in a density separation solution (choice determined by the type of plastics likely to be present), where less dense materials (e.g., microplastics) will float and separate from denser materials (sediment, debris, others) present in the matrix. There are a range of different reagents that can be used for density separation. These differ in their density, and each has advantages or limitations associated with efficiency for microplastic recovery,

varying levels of toxicity, and price ranges (Rani et al., 2023)(Table 5). These include sodium chloride, sodium tungstate dihydrate, sodium bromide, sodium polytungstate, lithium metatungstate, zinc chloride, zinc bromide, sodium iodide (Crutchett and Bornt, 2024). Higher density reagents are more effective at removing higher density polymers and are often employed when studying sediments, particularly those from intertidal and subtidal environments where heavier plastics sink and settle into the benthic zone. The density of the final solution used must be reported, as it will dictate which plastic polymers can or cannot be retrieved with this methodology.

To extract the microplastics using density separation reagents, the sediment should be transferred into a previously decontaminated glass beaker and the density separation reagent added. The sediment and density separation solution should be gently stirred with a metal spoon or glass rod and allowed to settle. Using a filtration kit (preferably glass or stainless steel), pour the supernatant over an appropriate filter (i.e., metal mesh, glass microfiber, silicon coated filter). The walls of the glass beaker should be rinsed liberally with ultrapure (e.g., Milli-Q) or filtered water to ensure all microplastic items are transferred to the filter. The loaded filter should be stored in a labelled Petri dish and covered with a glass lid. To identify microplastics, captured items should be observed under a microscope.

Table 5. Commonly used density separation reagents, highlighting their advantages and limitations.

| Density separation reagent | Density | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium chloride (NaCl) | 1.2 g cm-3 | - Recovers low density polymers (e.g., PE, PS, PP, PMMA, PC) - Cost effective - Non-toxic - Readily available |

- Less efficient at recovering high density polymers (e.g., PC, PU, PET, PVC, PTFE) |

| Sodium tungstate dihydrate (H4Na2O6W) | 1.4 g cm-3 | - Recovers low density polymers (e.g., PE, PS, PP, PMMA, PC) - Cost-effective - Non-toxic - |

- Less efficient at recovering high density polymers (e.g., PC, PU, PET, PVC, PTFE) |

| Sodium bromide (NaBr) | 1.37 g cm-3 | - Recovers a wide range of polymers - Non-toxic |

- Expensive |

| Lithium metatungstate (Li2O13W4-24) |

1.62 g cm-3 | - Recovers a wide range of polymers | - Expensive - Unknown effect on polymers |

| Zinc chloride (ZnCl2) | 1.5 - 1.7 g cm-3 | - Recovers a wide range of polymers | - Expensive - Toxic to the environment |

| Zinc bromide (ZnBr2) | 1.71 g cm-3 | - Recovers a wide range of polymers | - Expensive - Toxic to the environment |

| Sodium iodide (NaI) | 1.6 - 1.8 g cm-3 | - Recovers a wide range of polymers | - Expensive - Toxic to the environment |

| Calcium chloride (CaCl2) | 1.5 - 3 g cm-3 | - Recovers a wide range of polymers | - Expensive - Toxic to the environment |

| Potassium Iodide (KI) | 1.7 g cm-3 | - Recovers a wide range of polymers - Non-toxic |

- Expensive |

Biota

IMPORTANT NOTE: Prior to conducting any work on marine or coastal biota in relation to plastic and microplastic contamination, you must confirm what the permit, ethics, biosecurity, and work health safety requirements are for each specific species of interest. On confirming what is required, no work on marine and coastal organisms should begin until all relevant authorities have granted approval and formal documentation has been attained. Please assess both state and federal requirements.

Pre-Survey Preparations

The methods to acquire samples (i.e., capture, collection) of aquatic biota for microplastic assessment may vary according to the environment (e.g., pelagic vs benthic) and status (e.g., live vs dead) of the target species. The information in this section is organised into distinct sampling approaches tailored to major categories of marine and coastal biota.

Monitoring microplastic in marine and coastal biota

Analysis of microplastics in aquatic biota is generally conducted under one of the following overarching themes:

-

To monitor microplastic presence in the aquatic environment. Bioindicator species, such as bivalves (e.g., mussels, oysters) or plankton, can accumulate microplastics and reflect the presence of contaminants in the ecosystem. Analysing these species over time and space, allows assessing the extent and variations in the presence of microplastics in coastal and marine ecosystems to be assessed.

-

To investigate microplastic occurrence, accumulation and impacts on biota and across food webs. This involves examining, for instance, the ingestion, accumulation, and potential biological effects of microplastics on organisms, including bivalves, fish, marine mammals, and seabirds, among others. These investigations generally aim to assess the risks posed by microplastics to species and to provide valuable insights into the broader ecological implications of microplastics. This includes biota sampled opportunistically, such as carcasses of deceased individuals, and investigation of plastic presence in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT).

At the time of writing, microplastics have been detected in 1,565 species of wild animals (Santos et al., 2021) from aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, and this number continues to grow as more species are assessed. However, approaches to monitor microplastics in different biota differ widely due to the inherent differences in size, morphology, digestion, the way the species interact with plastic, the species accessibility for research, animal ethics considerations and permissions, as well as the cultural norms/attitudes surrounding research on different taxa. This is especially the case when it comes to lethal sampling designs, which are sometimes utilised to achieve non (or less) biased sampling for plastic ingestion research, given that many species reduce or alter their feeding behaviour before death. Non-lethal and opportunistic sampling designs can also yield valuable information on microplastic exposure without the need to sacrifice living animals, although these designs are also prone to sampling biases, which will be explored later.

Generally, it is more common to conduct targeted lethal microplastic exposure baseline and monitoring sampling designs on smaller organisms such as smaller invertebrates (non-cephalopods), although there are exceptions. Lethal sampling designs typically involve the collection or harvest of live animals for the explicit purpose of scientific research. These animals are sacrificed, and plastics contained within them are separated from the organic matter through chemical digestion of the entire animal, post necropsy, or from GIT contents (i.e., ingesta and digesta), and then microplastics quantified. Non-lethal sampling designs, on the other hand, are usually employed when investigating larger organisms (non-fish vertebrates). These often involve either the collection of scats/faeces or regurgitated material from living animals, which can be collected from the environment, or by capturing the animal to procure the sample (i.e., via gastric lavage, or as part of routine health assessments).

Opportunistic sampling designs are common for larger vertebrates, especially those that are either logistically difficult to access (for example rare or dispersive species) or where ethical and cultural values would curtail permissions to disturb the animal or its habitat for microplastic research (e.g., threatened and otherwise protected species). Opportunistic sampling design often involves the collection of carcasses of animals that have died of natural/incidental causes, been euthanised for veterinary/welfare purposes, or killed for a purpose that is removed from research goals such as aquaculture, wild harvest or by-catch of harvest for human consumption.

While it is not feasible here to include a sampling design for all the species that are investigated for microplastic research, general principles of sampling design, microplastic separation and plastic characterisation and reporting apply. Included here are the main general principles and an overview of approaches for different taxa.

Species selection

For vertebrates, most of the microplastic research around the world has used opportunistic samples, typically necropsy of animals that have died due to a variety of causes. Opportunistic samples are typically sourced from beach-cast individuals, euthanised for welfare purposes, or by-catch (and deceased) in fishing and other commercial activities. However, the number of animals that can be sourced this way in Australia is generally low, not only because of the low numbers of animals dying, but also a lack of organised, accessible centralised systems for reporting and collecting carcasses (e.g., centralised beach monitoring networks, though some jurisdictions have local, site-level or informal citizen-science monitoring networks), which is the case even if the scope of sampling effort is Australia-wide. For example, fisheries by-catch is only reported in specific fisheries, or when there are observers onboard, and carcasses of by-catch animals are typically discarded at sea rather than collected for scientific purposes. For cetaceans, it is unlikely that more than ten individuals are likely to be procured each year unless there is a mass mortality event, such as a mass stranding. It is important to note that permits are still required to investigate these animal carcasses. Therefore, for sampling wild organisms, it is important to plan ahead for the logistic reality of potential low sample numbers, difficulty achieving scientifically robust replication, stratification, and other best practice sampling goals.

The following criteria should be considered when selecting species to investigate and/or monitor:

- Naturally occurring species with a high abundance,

- Species for which robust sampling and processing methods are already established,

- Ease of sampling and laboratory processing,

- Species already commonly used as bioindicators in other areas of research, i.e., marine pollution and conservation monitoring programs,

- Species of ecological, socio-economic and cultural importance,

- Species with a broad coverage of ecological niches, and feeding types,

- Species that do not require ethics for sampling (e.g., those not considered sentient),

- Or, species for which structured/standardised sampling already occurs, and for which the addition of microplastic sampling is possible.

As an example, bivalves are a popular choice given that they fulfil most of these criteria (Ding et al., 2021; Li et al., 2019):

- they are not currently considered to be sentient,

- do not require ethics,

- are common in intertidal zones and coastal locations globally,

- are relatively easy to collect from the wild,

- can be sourced from commercial growers or raised in laboratory settings,

- have high economic and ecological value, and

- there is a plethora of literature describing validated methods and their successful implementation in biomonitoring programs.

Other species that have been used as indicator species include small fish (specifically, by sampling their GIT contents) and sediment-dwelling organisms (e.g., worms). A review of plastic bioindicator literature for the North Pacific identified a suite of 12 candidate bioindicator species covering a variety of ecosystem components and a wide range of plastic size classes, including two bivalves, three fish and two sea turtles species that are also present in Australia (Savoca et al., 2022).

Note on Listed marine wildlife (EPBC Act, Marine and Migratory or Threatened)

Marine mammals, marine turtles, sea snakes, and several species of seabirds and elasmobranchs are listed as Matters of National Environmental Significance (EPBC Act). This means they are subject to many levels of protection and there is a high barrier for entry for disturbance of these taxa for research generally. Due to this, lethal sampling methods for protected species are very unlikely to be permitted by any authority in Australia. Non-lethal sampling methods are difficult to apply to vertebrate marine wildlife that do not routinely regurgitate, and whose faeces are passed in the seawater, making scat collection logistically difficult.

Sampling design

General principles

The first thing that must be considered before commencing field sampling is what question(s) are you trying to answer (see What are the specific goals of my research?). Different research questions may require different sampling designs and most likely different sample collection methods. Refer to the Survey Design SOP for further details. Sampling designs should also ensure post-survey requirements are adequately considered, as well as the time required to accurately process microplastic samples from biota. Overall, sampling design principles are similar irrespective of whether you are seeking to use biota as a proxy to monitor for the presence of microplastic in the environment or whether you are specifically concerned with monitoring microplastic impacts on specific biota.

Sampling frequency is also dependent on the research question and species being investigated. If variations over time or between seasons are under question, then multiple sampling efforts across seasons or time are required. Ideally, replication is required within each spatial or temporal unit of interest. If simply trying to quantify whether microplastic is present, then a single targeted sampling effort may be appropriate. Notwithstanding, following these guidelines will ensure the comparability of microplastic data from biota.

Pros and cons of designed vs opportunistic sampling

Designed sampling approaches

Biota can be sampled through structured designed sampling approaches - for example, the targeted harvest of a species through a well-planned sampling design.

Examples of designed sampling approaches include:

- Bivalves placed in sea cages at predetermined distances from a river mouth to monitor the reach of microplastic outflow.

- Microplastic loads in polychaete worms sampled in the intertidal zone every kilometre along a coastline of interest.

- Microplastic load in every 50th sardine harvested from wild-caught sardine fished commercially for human consumption.

- Microplastic frequency and loads in scats collected weekly over 12 months across a suite of pinniped colonies.

Strengths

- Careful control over sampling design means that robust sampling principles such as stratification, randomisation, replication and adequate sampling power can be built in at the design phase,

- Allows for standardisation and comparability,

- Often larger sample sizes, i.e., can assess multiple individuals of a population at any given sampling time,

- Can assess how representative the sample is of the wider population,

- Suitable for long-term monitoring to understand trends in microplastic concentrations, and

- Ideal for differentiating any observed trends.

Weaknesses

- Often inappropriate for studies involving whole-organism examination, such as the necropsy of vertebrates (except for fish harvested for human consumption) due to the ethical and legislative hurdles of collecting/harming/disturbing these species for a research purpose,

- Not suited to the investigation of threatened or endangered species in the event biota is sacrificed, and

- Sampling to achieve adequate replication likely to be resource intensive.

Opportunistic sampling approaches:

Biota can be sampled through structured or non-structured opportunistic sampling approaches, for example, the collection of carcasses as they become available.

Examples of opportunistic sampling approaches include:

- Microplastic frequency of occurrence, load and characteristics across a suite of by-catch species available through commercial fishing,

- Microplastic frequency of occurrence, load and characteristics in pilot whales sampled during a mass stranding event,

- Microplastic frequency of occurrence, load and characteristics sampled in carcasses of seabirds and sea turtles that died in care at a marine animal rescue centre, and

- Microplastic frequency and loads in scats collected during a single trip to a pinniped colony.

Strengths

- Opportunistic access to rare species and species that move that are difficult or not possible to sample live in the wild, for example, beach-cast animals, stranding events and by-catch of cetaceans, sea turtles and seabirds,

- Opportunistic access to species that ethical permissions would not be granted for targeted disturbance or harvest, for example, threatened species and those covered by legislation for example, protected by the EPBC Act 1999,

- Can provide preliminary data on previously under investigated species, and

- Is often cheaper.

Weaknesses

- Prone to sampling biases such as single populations, discrete geographic areas, and other local conditions/contexts that may not be appropriate to generalise,

- Prone to biases affecting the behaviour of the animal before collection, for example, sick animals that become beach-cast may not be feeding normally before death,

- Often smaller sample sizes, i.e., can be a single individual, and

- Difficult to assess how representative the sample is of the wider population and to determine variability.

Field Procedures

Materials and equipment for sample collection

The vast range in size (e.g., from invertebrates to whales), life cycles, anatomy and environment (pelagic vs benthic) of aquatic biota species means that the tissue or type of sample collected varies greatly (Table 6). Likewise, biota can be sampled directly from the environment or from fisheries and aquaculture. Therefore, specific consideration of taxa traits and their habitats is needed to determine the most appropriate collection method – some of these include trawl nets, cages, line, or hand collection by snorkel or SCUBA (Zantis et al., 2021) (Table 7).

When collecting any sample from marine and coastal biota (from plankton to whales, and benthic to pelagic) or faeces, scat and regurgitate, whether in the field or captivity, it is essential to implement measures to reduce contamination during the collection (e.g., reducing risk of contamination from collection gear; rinsing of external bodies to remove adhered environmental microplastics) (Lusher et al., 2017). Where possible, organisms should be individually weighed, and size measurements taken prior to the dissection and/or extraction of any tissues. If specific dissected tissues are being analysed for microplastic content, these should also be weighed. Samples should be stored in clean, plastic-free containers (preferably in glass) in clean areas, and processed in a clean laboratory environment (see the Quality Assurance and Quality Control (QAQC) section below for more details).

To correctly represent a population, an appropriate sample size that takes into account the research unit (e.g., species, food web, feeding type) needs to be selected. Power analysis is strongly recommended when planning collections and experimental designs. It is important to consider what would be an appropriate effect size. Before commencing sample collection, a power analysis can be performed to assist in this decision. G*Power (Faul et al, 2007) or pwr package in R (Champley_ et al._ 2020) are suitable for simple sampling designs and can determine the number of samples required to achieve the desired effect size. Sample sizes can be smaller if appropriately justified (e.g., organism availability, statistical power analysis, and monitoring constraints), e.g., see Lavers et al. (2021) for a power analysis calculated to sample microplastics in birds.

Table 6. The type of sample that can be collected for analysis of microplastics by organism type. This table is a reference only. Literature reviews and targeted preliminary and further research are required to confirm that the sampling method is appropriate for the organism of interest and suited to the downstream analyses. PPE - Personal Protective Equipment. The ✓in the table indicates the method(s) that can be used for the aforementioned categories.

| Sample Type | Cetaceans & Dugongs | Pinnipeds | Marine Turtles & Marine Reptiles | Marine Birds | Fish & Elasmobranchs | Bivalves | Larger Crustaceans | Pelagic Invertebrates | Benthic Invertebrates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole organism | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Trawl | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Faeces | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Opportunistic necropsy | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Opportunistic regurgitation | ✓ |

Table 7. Equipment that is required for field sampling of different aquatic biota groups. This table is a general guide as each sampling strategy will have variations in equipment and sampling requirements.

| Sampling Method | Cetaceans & Dugongs | Pinnipeds | Marine Turtles & Marine Reptiles | Marine Birds | Fish & Elasmobranchs | Bivalves | Larger Crustaceans | Pelagic Invertebrates | Benthic Invertebrates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Permits | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | * | ||

| Ethics | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | * | * | ||

| PPE | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Trawl net | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Fishing gear | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Quadrant & relevant equipment | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Coring equipment | ✓ | ||||||||

| Netting | ✓ | ||||||||

| Sample collection and storage equipment i.e. Glass jars (appropriately cleaned) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| General field equipment (Datasheets, labels, pencils) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Camera and GPS |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

*Cephalopods require ethics approval and may need a permit in some jurisdictions.

Common cross-taxa processing approaches and opportunities for harmonisation

Across the different taxa, there are several common approaches to sample processing and analysis. For general information on standard microplastic separation protocols, see the detailed post-survey sections below, which include details on visual inspection, separation of microplastics from organic matter using chemical/enzymatic digestion and/or density separation, and visual and chemical identification of microplastics. Many of these protocols are suitable for numerous species and tissue types and offer compelling starting points and significant opportunities to increase harmonisation in sample collection, processing, and reporting. These include:

- Necropsy procedures for large animals (cetaceans, sea lions and large sea turtles)

- Necropsy procedures for medium sized animals (sea birds, small sea turtles, large to medium fish)

- Chemical digestion of ingesta and digesta

- Chemical/enzymatic digestion of soft tissues (GI tracts of fish and large crustaceans, soft body of bivalves, soft-bodied pelagic and benthic invertebrates)

- Chemical digestion of chitinous species (small crustaceans, hard-bodied pelagic and benthic inverts)

- Chemical/enzymatic digestion of whole animal (small fish, fish larvae and sponges)

- Collection and digestion of faeces and scats

- Microscopy protocols

- Polymer identification

However, given the diversity of taxa and sample types (e.g., tissues, faeces, scat, regurgitate) that are now being investigated for microplastics presence and quantification, specific considerations must be given to taxa- and sample-specific protocols for downstream sample processing. Furthermore, in many cases, published protocols are not available and there is a need to establish and validate methods before use (Santana et al., 2022).

Taxa-specific collection and processing strategies

Cetaceans and dugongs

Sampling cetaceans and dugongs

Notwithstanding their iconic status and protection in many jurisdictions globally, cetaceans and dugongs are not ideal candidates to monitor or research microplastic because they are large and logistically difficult to work with.

Most microplastic sampling studies of cetaceans come from the collection and processing of faeces and gut contents from smaller live wild species (i.e., dolphins), and through the necropsy of by-catch, beach stranding and other cetacean carcasses (Lanyon, 2010). It should be noted that many cetacean species move, which means that the plastic data collected may not accurately represent the location of capture/sampling.

Separating plastic from organic matter

For cetaceans, necropsy is the primary method of separating plastic from organic matter, specifically, via post-mortem examination of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT). There are numerous cetacean post-mortem assessment protocols worldwide (Ijsseldijk et al., 2019; Mazzariol and Centelleghe 2017; Plön et al., 2015). For Australia, please refer to the Australian Government’s standardised protocols (Australian Government, 2006).